“But the genius of this memoir lies in its letting us see how much the narrator becomes his father rather than struggles to separate from his father.”

Vivian Gornick, The Situation and the Story: The Art of Personal Narrative

When I read the quote cited above, I underlined it with my black pen, hard, and drew a big star next to it. Big stars mean business. Big stars make it easy to find what matters to me in a book long after I’ve read it.

When I drew that star, and every time I reread the quote, my heart turns icy. For me, this is terrifying. I can’t bear the idea that I would become my mother, yet I can bear it, otherwise I wouldn’t draw a star next to Gornick’s sentence.

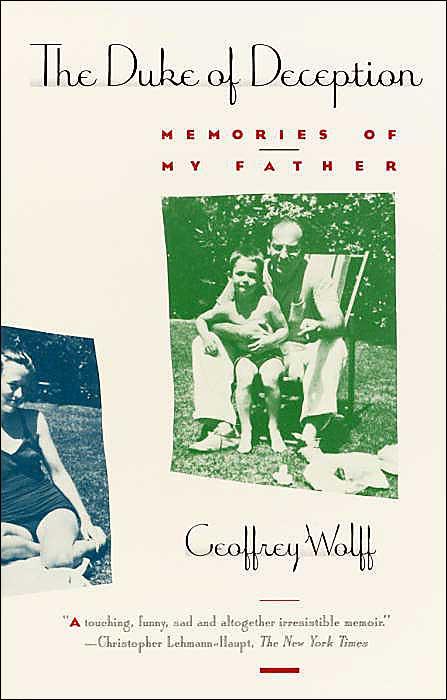

In her analysis of Geoffrey Wolff’s The Duke of Deception: Memories of my Father,” Gornick describes Wolff’s relationship with his father as “a complication of attraction-repulsion.” Wolff both admires and reviles his father as “a bullshit artist” who fabricated a background of high-class education and sophistication to satisfy a need to “have the best and not pay for it.”

Yet Wolff must reckon with his own his own false narrative, the one he creates as a young man who “apes the look and style of the rich and socially connected.” He learned from his father how to charm; how to go for what he wanted the moment he wanted it; how to make up any excuse or lie in service of his own selfish desires.

I’ve been writing personal narrative long enough (and had enough therapy) to do my own reckoning with what I’ve inherited from my mother and father. What strikes home for me right now, as I’ve written about free drafting and fast free-writing and writing through the difficult sections in memoir is that those sections take place in my young, not-so-self-aware life.

It was in my teens and twenties that my mother’s influence most strongly manifested in me in a dysfunctional way. I was terrified of abandonment and projected that onto the people I dated, creating unnecessary tension and drama. I couldn’t bear to be wrong about something, because that meant I was wrong about everything. I couldn’t stand to be left, because that meant everyone would leave me.

There was no between. It was all or nothing. I was either good or bad, lovable or unlovable, genius or stupid. It is a horrible, painful, exhausting way to live.

The difference between my mother and me is I was able to objectify my experience enough to see that it was dysfunctional and to recognize that my behavior was my responsibility. Maybe I could change it. Maybe I had that power. I spent many years and a lot of energy doing just that. If I hadn’t, I wouldn’t be able to write what I’m writing in this moment.

Still, when I’m crafting narrative from my life, my psyche resists the scenes which echo my mother’s traumatizing behavior. Any seasoned memoirist will tell me that these are exactly the scenes in which I must lean in, a phrase I heard often lately.

So here I am, leaning in. Ugh, you guys, it is tough. But I have to admit, it is strangely rewarding to be learning that it’s okay. It’s another thing that feels terrifying but is completely survivable. It just makes me more human.

I understand! I wake up at night stewing over something I did that reminded me of my mother. A constant battle even with the self-knowledge. Great piece, thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a difficult thing to embrace. To love ourselves regardless of that awareness. I’m still working on it 🙂

LikeLike